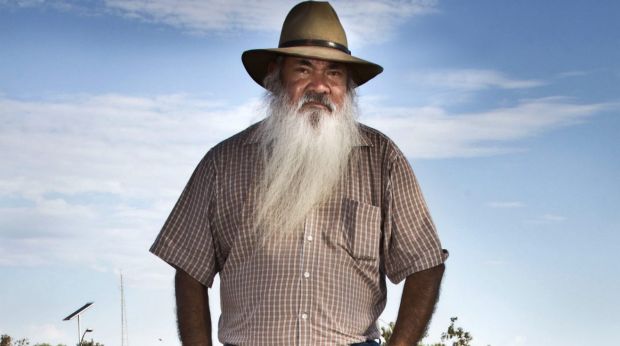

Aboriginal elder Pat Dodson: portrait of the senator as a young man

Paddy Dodson might have been just another scared kid on his first night at boarding school … if he hadn’t been black. He drew the bedsheet up to his nose and pulled his pillow over his head. All the other kids, 200 of them crowded into one huge dormitory, wanted to get a look at him.

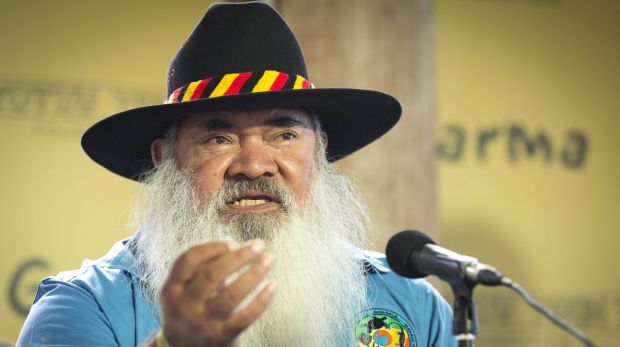

All of Australia has since got a look at Patrick Dodson, the bloke with the waist-length beard and the hat with its band of black, yellow and red, who has spent much of his life working for a better deal for Australia’s First People. We’re about to see more of him, for he’s Labor’s new senator for Western Australia. It’s a bit of a surprise to those who’ve known him for a while.

Politicians tend to be a bit tentative,” he told me a few years ago during a long yarning session. “They see life in terms of three-year brackets, not in terms of history.”

Pat Dodson is known as the Father of Reconciliation. Photo: Peter Eve / Yothu Yindi Foundatio

Paddy Dodson, however, has always been capable of surprising, and at 68, he might be able to teach politicians a bit about seeing things in longer time frames.

Those curious boarding-school kids way back in the 1960s learned pretty quickly that the first Aboriginal student at their school was much more than they imagined. He didn’t know what a bread plate was, or a butter knife, but life had already thrown bigger and harder lessons at him. Born in Broome to an Irish-Australian father, Snowy Dodson, and an Indigenous mother, Patricia, his family had fled across state borders to Katherine, in the Northern Territory, when Pat was a two-year-old baby.

Pat Dodson will become Labor’s Senate candidate for Western Australia. Photo: Andrew Meares

The hounding laws of Western Australia had become too much. Even love was a crime. Snowy had been jailed for 18 months, years before, for “cohabiting with a native woman”, Pat’s mother. Pat had to grow up fast. Aged 13, he and his brothers and sisters – seven of them altogether – were orphaned. Their father died first, and then their mother, three months later. Pat and his brother Mick, who was aged 10, were in danger of becoming “stolen children”. Their aunt and uncle came and collected the children and took them to Darwin on the back of their Chevy truck.

“The protector of native affairs in the Northern Territory, a fella called Harry Giese, was poised to send me to one of the Catholic Missions,” Pat told me.

“Unfortunately the church, as often happens, couldn’t find the necessary resource to send me over the Strait (from Darwin to the Garden Point Mission on Melville Island) as the boat that was supposed to take me had sunk.” The Dodson children’s aunt and uncle, both of whom knew firsthand about life on missions, battled the authorities in and out of court to keep the little family out of the clutches of authority.

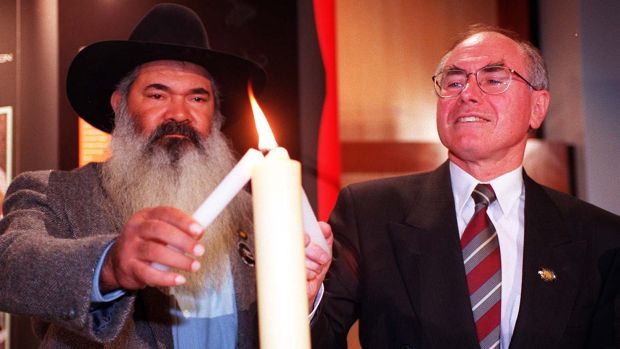

Chairman of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Pat Dodson lights a candle with former prime minster Howard at a luncheon in the Great Hall of Parliament House to mark the start of Reconciliation week. Photo: Mike Bowers

Pat and Mick, however, and a brother and sister, Patricia and Jacko, were declared “wards of the state”, but in the care of family, though they were split up. Eventually, a couple of priests from the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart stepped in and decided to help the orphaned Pat and Mick to get as far away from the Northern Territory as possible. They arranged scholarships for Pat (and later Mick) to fly south, to Hamilton in far-west Victoria, to board at Monivae College, run by the MSCs.

And so, in the early 1960s, an Aboriginal boy found himself in an alien world, trying to hide in his bed down the end of a dormitory as 200 boys jockeyed to get a look at the most exotic student they could imagine. Paddy, as he quickly became known, didn’t hide away long. He emerged as a hard-studying and quietly powerful character, aware of high expectations thrust upon him at a time when no one knew anything about Indigenous affairs.

“There was always the search as to who was going to be the ‘first’ of this and the ‘first’ of that as if that was going to be the only ever achievement in this country,” he remembered.

He won the diligence prize five out of the six years he was at Monivae, became a middle-school prefect before Australia had even held a referendum concerning recognition of Indigenous Australians and formed tight friendships that endured.

By the time I arrived as a student at Monivae in 1967, Pat Dodson was captain of the school, captain of the all-but unbeatable First XVII and Adjutant of the Cadet Corps. He was an undisputed leader.

Pat and Mick (another leader, who became vice-captain and a House Captain) had no money. It didn’t matter. A fellow named Bill Walsh – the father of Phil Walsh, who became coach of the Adelaide Football Club and who was killed in tragic circumstances last year – ran Thompson’s Department Store in Hamilton. He simply provided the Dodson boys with uniforms, footy boots, casual outfits and sports gear. Other parents took the boys to their farms for holidays. Everyone knew the Dodson boys would make a name for themselves. But we couldn’t have guessed that Pat would become known as the Father of Reconciliation and win the Sydney Peace Prize, or that Mick would become Australian of the Year, and much, much else.

From little things….