If black lives really matter in Australia, it’s time we owned up to our history

Australia’s frontier had cruelty to rival the US south. That’s why a racialised insult against Adam Goodes has more power than a comment on Andrew Bolt’s blog

In the US, the Black Lives Matter campaign is forcing a long-overdue reckoning with that country’s history, with (in the wake of the Charleston massacre, in particular), activists launching a new conversation about the Civil War iconography that litters much of the South.

Already, the Confederate flag’s gone from the South Carolina state house. In Kentucky, talk’s turned to the removal of a Jefferson Davis statue. In New Orleans, pressure is building on the memorial to Robert E Lee while Memphis ponders the future of its multiple statues of KKK founder Nathan Bedford Forrest. In communities across the south, public history is suddenly up for debate.

The fissures revealed by the Adam Goodes controversy suggests the need for a similar project here. As it happens, in his new book Australian Confederates, journalist Terry Smyth draws out some fascinating connections between Australia and the American south.

myth focuses, in particular, on the 42 Australians who, in 1865, secretly enlisted to fight for the slave-owning states when the Confederate ship Shenandoah docked in Port Phillip Bay. In passing, however, he acknowledges the broader significance of the Civil War, which opened sudden opportunities for another nations to export agricultural crops.

As historian Kay Saunders has said, the northern blockade of Confederate cotton and sugar meant that “Queensland was regarded potentially as a second Louisiana”.

Aspiring local planters tried to seize the moment, inducing British mill workers to immigrate and establish a local cotton industry. But they quickly discovered that men from England’s industrial towns would not accept the conditions prevailing on plantations in the Australian rural north.

“In 1863,” Smyth writes, “shipping magnate and entrepreneur Robert Towns established a cotton plantation on the Logan River, in Queensland. Convinced that the venture would never turn a profit if he paid white man’s wages, he sent a schooner to the South Pacific to recruit Islanders. The ship returned with 67 Melanesian men who were put to work picking Towns’ cotton. ‘Kanakas’, they were called – originally Hawaiian for ‘free man’ but used by whites as a derogatory term akin to ‘nigger’.

“Although Towns’ islander labourers were offered wages, food and housing and a promise they could return home if they wished, the practice of so-called indentured labour, as it spread throughout eastern Australia, soon degenerated into a form of slavery called ‘blackbirding’.”

Australian South Sea Islanders at Farnborough, Queensland, circa 1895.

Between 1863 and 1904, 62,000 South Sea Islanders were brought to Australia, landing in Brisbane, Maryborough, Bundaberg, Rockhampton, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville, Innisfail and Cairns. The majority of the indentured labourers came from today’s Vanuatu, with a substantial proportion from the Solomons, as well as smaller islands. Some came voluntarily (even accepting multiple trips). Others did not – and varying degrees of deception and outright coercion were used by blackbirders to persuade them.

By the 1890s, the so-called “Kanakas” were providing 85% of the workforce for the sugar industry.

The conditions the Islanders faced in Australia were extraordinarily harsh.

Smyth describes a notorious case in which “a certain John Tancred was charged with stealing an islander boy named Towhey, the property of Arthur Gossett. The complainant swore he could prove his ownership of the boy because he had branded him not once but twice – on the leg and on the side – which he demonstrated to the court. The judge fined Tancred 10 pounds for theft, and Gossett walked way with his young slave in tow.

“The press report of the case heartily approved of the outcome, helpfully suggesting: ‘perhaps it may not yet be too late for the Assembly to insert a ‘branding’ clause in the Polynesian Labourers Bill.’”

Not all sugar growers conducted themselves like southern slave owners. But, by definition, indentured labour in Queensland was, as the academic Tracey Banivanua Mar argues, “a legalised system that bound mainly young men to three years of coercive labour under physical conditions considered to be fatal to Europeans, and in standards of accommodation and care that were largely negligent and often fatal”.

Between 1868 and 1889, Islanders’ mortality rate in Queensland was something like 19%. There’s no mystery as to why. In a July 1880 discussion of high death rates on plantations owned by R Cran and Company, the liberal Queenslander newspaper explained that the “the islanders were being killed mainly by overwork, insufficient or improper food, bad water, absence of medical attention when sick, and general neglect”.

If this history isn’t generally known, we shouldn’t be surprised.

At federation, the fate of the Islanders – many of whom had by that time lived in Australia for decades – was hotly contested. Edmund Barton, the first prime minister, argued for their deportation in order to preserve the racial purity of White Australia. In doing so, he explicitly referenced the experience of the American south.

“The negro cannot be deported now because of his numbers, and because his race has become rooted in American soil,” he said. “We do not propose that either of these conditions should ever arise in Australia.”

Thus a key piece of legislation in the first ever parliament was the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, which mandated the forcible deportation of 7,500 Pacific Islanders and banned the entry of any other Islanders after 1904.

“The country did not feel the need of the imported nigger before he came and his loss will not be felt when his gone,” explained the West Australian Sunday Times.

“We do the nigger no injustice by deporting him to his native land in better condition than when he left it.”

What does this have to do with Adam Goodes? A recent survey by regional newspapers in Victoria showed a great majority of respondents saw nothing racist about the hostility directed by fans at Goodes.

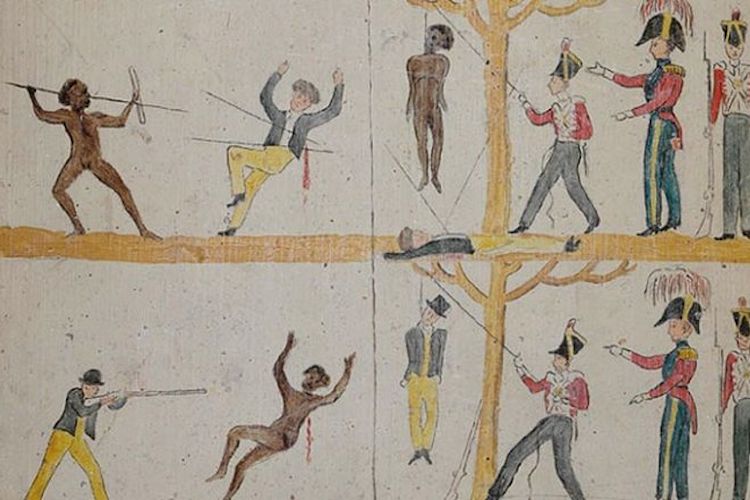

Godfrey Charles Mundy’s depiction of the 1838 Slaughterhouse Creek massacre. Illustration: Godfrey Charles Mundy/Australian War Memorial

In the US, many whites have reacted to the Black Lives Matter campaign with similar incomprehension. They’ve never had any trouble with the police – and they don’t see why the experiences of African Americans should be any different.

The debate about southern history taking place across America matters because it provides that missing context.

As Brent Staples says in the New York Times, the confederate monuments were mostly erected in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, during the period in which the former slave states were introducing, usually with great violence, so-called Jim Crow laws to abolish voting and other rights for African Americans.

The statues, in other words, were an adjunct to a racialised terror enforced by the police as much as by the KKK. That’s what Angela Davis means when she says “there is an unbroken line of police violence in the United States that takes us all the way back to the days of slavery, the aftermath of slavery, the development of the Ku Klux Klan”.

In the same way, white Australians might think nothing of being called an “ape”. But Goodes’s response to the taunt arises from a history that shares far more with the US south than we’d like to think.

In 1960, Faith Bandler, who would become a crucial campaigner for Aboriginal rights, met the legendary African American singer and polymath Paul Robeson during his only Australian tour. Robeson was the child of a slave.

So, too, was Bandler. Her father had been blackbirded from his island in the New Hebrides and then had escaped deportation by fleeing to northern NSW. Faith grew up in a country town shaped by de facto segregation – and, because of that, always identified with Robeson and other American civil rights activists.

She later recalled her meeting with him:

I had an occasion to … show him a film that was made on the Warburton Ranges. And I shall never forget his reaction to that film, never. It was a film taken on a mission station where the people were ragged and unhealthy and sick, very sick. And we took this film and we showed it to him. [A]s he watched the film the tears came to his eyes and when the film finished he stood up and he pulled his cap off and he threw it in his rage on the floor and trod on it and he asked for a cigarette from someone. Well a lot of people smoked in those days so there was no shortage of cigarettes and [his wife Eslanda] said to me, ‘Well it’s many years since I’ve seen him do that’. He was so angry and he said to me, ‘I’ll go away now, but when I come back I’ll give you a hand’. He was beautiful, but he died and he didn’t come back.

Robeson was a long-time campaigner for African American rights. He knew the appalling conditions in the deep south – but the situation facing Indigenous Australia still moved him to tears.

Indeed, historically, the local press openly acknowledged that Aboriginal people were treated far worse than even the Islanders imported to make Queensland a “second Louisiana”.

For instance, in 1880, the Queenslander launched a campaign against what it called “the sickening and brutal war of races that is carried on in our outside settlements”. This, it said, “is how we deal with the aborigines: On occupying new territory the aboriginal inhabitants are treated exactly in the same way as the wild beasts or birds the settlers may find there.”

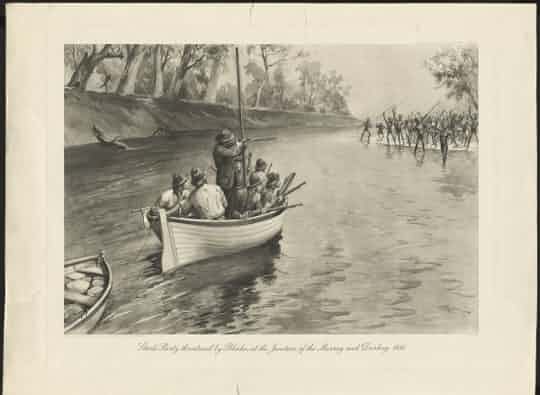

‘It’s very rare – indeed, almost unheard of – for towns to acknowledge the men, women and children killed not in France but here in Australia defending their land against settlement.’ Photograph: Nla

A prolonged debate ensued in its pages, with some correspondents minimising or justifying the violence, and others providing astonishingly frank accounts of frontier atrocities.

On 2 October 1880, for instance, one contributor wrote:

I am no sentimental black protector, and have lived in this Cook district since 1873, when it was first settled. … We are in this district in a state of open warfare with the natives, and if I met a mob anywhere in the bush I should feel justified in firing on them. But there are things done to blacks and black women by some of the police which equal the Bulgarian atrocities that thrilled Europe with horror. In this district a cattleowner who often has to do his own ‘dispersing’ made a raid about a year ago on the blacks, and captured a young gin. She was brought home to the station, and was employed carrying water from the river to the house during the day, and at night was chained by the leg to a verandah post, to prevent her escaping and to ‘civilize’ her. One of the boys employed on the station took a fancy to her, and she was looked on as his wife.

He goes on to outline, in the polite euphemisms of the 19th century, a horrific account of sex slavery and gang rape.

The series of articles concluded on 20 November 1880 with the editorialist writing:

[P]roperty acquired by conquest, no less than that which is transmitted by inheritance, has its duties as well as its rights, and … we, in common with the other States on this continent, have shamefully fallen short of our duty towards the inferior race whom we have dispossessed. That it should be necessary for any section of the Press, in order to ensure a hearing at all, to argue on purely utilitarian grounds against the policy of deliberate extermination that has been unremittingly pursued hitherto; that it should have been incumbent on us to lay stress, not so much on the wickedness and cowardice as on the unprofitableness of shooting down like vermin the helpless savages whose homes we have invaded – all this is evidence of a blunting of the moral perceptions of our own community such as would appear morbid and unnatural if manifested in any other sphere of human relations.

The peculiar reference to “unprofitableness” probably harks back to a debate in the Queensland parliament in the previous month.

There, on 21 October, the MP John Douglas (who would later go on to become premier), had explained, as Hansard put it:

The colony was now introducing Polynesians, and he did not believe that there was any such great distinction between them and the aborigines of Northern Australia as to prevent the hope that some use might be made of the latter. In Western Australia the natives had been, he believed, in some cases captured, and as prisoners of war had been compelled to submit to a period of pupilage, afterwards becoming useful settlers. … It would be quite possible to take the natives prisoners, instead of shooting down and killing them, though he doubted whether the House would sanction a law by which these people, taken in open warfare, might be kept in a state of captivity. At all events, that would be a more benevolent process than shooting them down and taking their lives. No doubt to shoot them down was the easiest way of getting rid of them.

Here, then, was the liberal position: Queenslanders should cease murdering Indigenous people. Instead, they should enslave them, thus sparing themselves the necessity of blackbirding indentured labour.

That’s the context in which a racialised insult flung at Goodes possesses rather more power than, say, the mean remarks that Andrew Bolt sometimes finds in his comments threads.

In his recent book Forgotten War, Henry Reynolds notes the obvious disparity between Australia’s commemoration of the first world war (something that has now cost nearly half a billion dollars) and the almost complete indifference shown to the frontier wars fought by settlers against Indigenous people, even though the latter possesses far more significance in the development of the nation.

Just as most towns in the American south boast a cairn to the Confederate dead, every tiny community in regional Australia has its a shrine to the dead of the Great War. But it’s very rare – indeed, almost unheard of – for towns to acknowledge the men, women and children killed not in France but here in Australia defending their land against settlement.

As Reynolds says, the Australian War Museum honours farcical engagements like the Sudanese war but makes no reference to the “sickening and brutal war of races” the Queenslander so openly discussed, even though the frontier war was clearly the most important conflict in Australian history.

Tony Abbott famously thinks that, before the arrival of Europeans, Australia was “nothing but bush”. It would be foolish indeed to expect the prime minister to commemorate people he seems to believe never existed.

But what’s fascinating about the debates taking place in the US is that they’re driven by ordinary people rather than politicians. The Confederate flag at South Carolina’s State House was first lowered not by a legislator but by African American activist Bree Newsome, who went to jail as a result. All across the country, it’s Black Lives Matter campaigners who are insisting on a discussion of the nation’s history, precisely because that discussion necessarily intersects with politics today.

The Frontier Wars in Australia were fought out with different tactics in different places at different times. Remembering the conflict thus necessitates localised histories, specific accounts of what was done in specific places. An official statement about the past is all too likely to dissolve into platitudes and empty symbolism.

But a grassroots campaign to identify and commemorate particular histories would take on a different dynamic. It would necessitate an engagement with the community, for a start: a serious public debate about historical injustice. It would also link the past with the present, inevitably posing questions that go beyond the treatment of Adam Goodes into the shocking statistics about, for instance, Indigenous unemployment and incarceration.

Australian history and American history are not the same. But it’s very hard to read, say, Amy McQuire’s account of the death last year of Julieka Dhu in police custody without asking the questions currently being posed in the US: do black lives matter or not?