‘We are all entrepreneurs’: Muhammad Yunus on changing the world, one microloan at a time

This week Professor Muhammad Yunus visits Australia. Professor Yunus received the first-ever Sydney Peace Prize in 1998, eight years before winning the Nobel Peace Prize.

Events and lectures are sold out, but Professor Yunus will appear on ABC Q&A on Monday 3 April. Tune in at 9.35pm AEST, or watch via ABC iview.

This article, written by Miriam Cosic, appeared in The Guardian on Tuesday 28 March.

Muhammad Yunus, the Bangladeshi economist, microfinancing pioneer and founder of the grassroots Grameen Bank, has not been resting on his laurels since wining the Nobel peace prize in 2006.

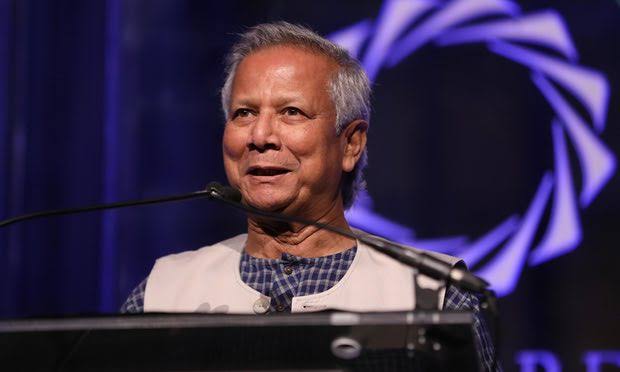

Professor Muhammad Yunus. Photo credit – Getty Images

For one thing, he has expanded his concept to developed countries via Yunus Social Business, founded in 2011. “Globally, the issues are the same,” he says. “In terms of poverty, of welfare recipients, of housing problems, water problems, in terms of healthcare problems. These are common problems, rich country or poor country. Australia has poor people, America has poor people, Europe has poor people.”

In the past year, he has begun establishing Yunus Social Business centres at universities around the world, including at Australia’s University of New South Wales and Latrobe University. Two centres are slated to open in New Zealand this year.

“Young people have to know about it,” he says. “They should learn that there are two kinds of businesses in the world. One is a business which makes money, and the other solves the problems of the world. It’s an academic exercise and what they do with that in real life will depend on them, what kind of life they would like to choose.”

Yunus is speaking to the Guardian on the eve of a trip to Melbourne for the Australasian Social Business Forum. The event is titled “Positive Disruption: Lead the Change”.

Disruption? Teased for being a Marxist, a revolutionary, a danger to society even, Yunus says: “Revolution is no solution. What do you do after the revolution? You have to figure out the purpose of the revolution. You don’t want to go back to communism, that didn’t solve any problems.”

Yet capitalism isn’t working for him either. The idea behind his multi award-winning idea of microcredit is that everyone is a natural entrepreneur. We tend to think entrepreneurs are those who succeed in a globalised financial system that is rapidly re-establishing the extreme inequalities that western governments legislated to limit in the 20th century.

Human beings are not born to work for anybody else

Yunus cites the oft-quoted statistic that one percent of the population of rich countries owns 99% of the wealth. “And every day it’s getting worse,” he says. His radical idea, established in poverty-stricken Bangladesh in the 1970s, was that if poor people were given a proper start and encouragement, their natural entrepreneurship would flourish.

“Human beings are not born to work for anybody else,” he says. “For millions of years that we were on the planet, we never worked for anybody. We are go-getters. We are farmers. We are hunters. We lived in caves and we found our own food, we didn’t send job applications. So this is our tradition.

“There are roughly 160 million people all over the world in microcredit, mostly women. And they have proven one very important thing: that we are all entrepreneurs. Illiterate rural women in the villages, in the mountains, take tiny little loans – $30, $40 – and they turn themselves into successful entrepreneurs.”

He points out that entrepreneurship is a particular boon for women, whose family duties – which they still shoulder even in more egalitarian western countries – make the nine-to-five world difficult.

Professor Yunus addressing the Sydney community during his 1998 visit

In the mid 70s, as a young economics professor, Yunus experimented with lending a mere $27 to 42 women in the village of Jobra near his university in Chittagong. Banks would not lend to the poor, fearing default, and moneylenders charged extortionate rates. His experiment was a success, and he began to develop the idea, in practice as well as in theory, eventually establishing the Grameen Bank.

At 76 years old, Yunus is still enthusiastic, despite fighting roiling political criticism in Bangladesh, spearheaded by prime minister Sheikh Hasina. Yunus has been accused of everything from having an autocratic management style to embezzlement and tax fraud. In 2011, the government moved to have him removed as head of his bank, formally citing his age. More seriously, perhaps, a vocal school of economic thought disagrees that microfinancing can enrich the poor.

Nonetheless, the Grameen Bank today has nine million borrowers, 97% of them women. “They own the bank. It is a bank owned by poor women,” he says. “The repayment rate is 99.6%, and it has never fallen below that in our eight years of experience.” Part of his expansion into rich countries includes a program in the US: 19 branches in 11 cities, including eight in New York. “We have nearly 100,000 borrowers there now and 100% women. Not a single man.”

Globalisation and the technological revolution may make Yunus’s theory timelier than even he expected when he began. Globalisation has sent manufacturing from rich countries to poor, and robots will eventually kill many of those jobs too as corporations seek to minimise costs and maximise profits. In rich countries, jobs are more precarious, people no longer expect the security of a job for life, and welfare is rapidly being reduced by the vogue for austerity economics.

Fostering entrepreneurship is the solution, Yunus says. And his concept of social business – created for pro-social goals, not profit – is the solution to social and environmental problems caused by intense capitalist competition. Some pioneering companies are already embracing it. Their reasons – genuine benevolence, good publicity, “greenwashing” – hardly matters, he says.

France is a leader. Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, wants to make her city a hub for social businesses. She has committed to making it a central feature of the 2024 Olympics if Paris wins its bid. “Many French businesses created social businesses on their own, running parallel to their conventional business,” Yunus adds.

Danone, the French dairy company, was one of the first, agreeing to form Danone Grameen in 2007 to produce fortified yoghurt for malnourished children in Bangladesh. The water company Veolia made a similar joint venture to provide safe drinking water in Bangladeshi villages, while the American food company, McCain, has a joint venture with Grameen helping farmers in Colombia raise crop yields. India is preparing to launch an “action tank” as Yunus calls it – a group of businesses that collaborate to create social enterprises on the side.

The bulk of the investment in these partnerships comes from the company, which expects no profit: it only takes back the amount of their investment over a period of time. “We just participate in a token way,” Yunus says. “A thousand euros or something like that, but we allow the name to be attached to the company to show that this is a genuine social business.”

Yunus maintains that people working in these sorts of businesses get a feel-good reward on top of their salaries. “Even shareholders start enjoying it,” he adds. “They don’t mind earning a little less if it is helping the children of the country, or poor people, or single mothers. They are proud that their company is taking care of that.”