Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz declares war against ‘know-nothing’ Trump

American economist and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz has been talking about the dangers of inequality since the 1960s. That a prime beneficiary of the growing chasm between rich and poor now occupies the White House is beyond galling to him. It’s war.

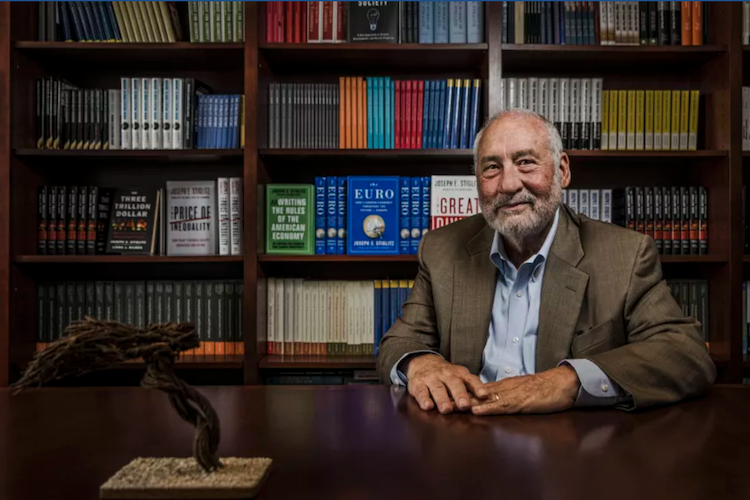

This article is written by Nick Bryant (SMH Good Weekend) and the cover photo is by Sasha Maslov and features Joseph Stiglitz in his office at New York’s Columbia University. The winner of this year’s Sydney Peace Prize, he says of Australia’s recent political stoushes: “Your car crashes are little nicks. America’s car crash is potentially fatal.”

Growing up, Joseph Stiglitz bore witness to America’s economic future. The decline of the once-mighty industrial heartland. The hollowing-out of Rust Belt communities. The decimation of the middle class. The chasm not just between rich and poor, but the rich and the rest.

The Nobel laureate in economics, who wore hand-me-downs from his elder brother that were clothes bought by his mother off the sale rack, came of age in Gary, Indiana. Even then, back in the supposed Golden Age of the 1950s, the struggling steel town was becoming part of a post-industrial landscape that provided a seedbed for Donald Trump. “I saw the case studies before people gathered the data,” says Stiglitz, whose writings over the past 50 years about the growing income gap in the US economy now read like forewarnings of President Trump’s rise.

“In 2015, I went back to my 55-year high school reunion, and had a chance to see what had happened to my classmates. It was the story of the failed American dream. Kids who said, ‘I wanted to go to college, but I couldn’t afford it.’ ‘I wanted to have a good job in the steel mill but we were going through an economic downturn so I had to go into the military.’ So you saw in kid after kid, classmate after classmate, their modest dreams had not been realised. This was a year before Trump’s arising, and my wife and I said, ‘This is Trump. This is fodder for somebody like Trump.’ “

A lifelong progressive, who as a student ventured into the segregated US South to participate in the struggle for black equality, Stiglitz regards Trump’s presidency as a national calamity. “Trump is so upsetting personally. As a young kid, I was very much engaged in the civil rights movement, and was at the March on Washington [in 1963 in which Martin Luther King delivered his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech]. This has been integral to my identity. And now having a bigoted president, I can’t tell you how devastating that is. It’s war.”

“Trump has tried to destroy our institutions, one by one, undermining the judiciary, the press, the intelligence agencies, the universities … every one of our major truth institutions.“

It sounds peculiar to hear this declaration of hostilities from a bespectacled 75-year-old professor, with a grey, stubbly beard and smiling eyes, who looks like a much-loved rabbi. He issues it as he munches on a garden salad in his office at Columbia University on New York’s Upper West Side, a room with five separate bookshelves stacked and stuffed entirely of his own works – tomes that have made him one of the world’s most widely read economists. The Price of Inequality. The Great Divide. Making Globalisation Work. Fair Trade for All. Freefall: America, Free Markets and the Sinking of the World Economy. Globalisation and Its Discontents. The titles, published in a superfluity of languages, offer a neat summation of his life’s work. So he must be struck by the irony that the political beneficiary of the vast discrepancies in income has been a billionaire who successfully rebranded himself as a working-class hero?

“In my book The Price of Inequality I basically said that unless we did something about this, it would have political consequences. I had in mind something of the ilk of Donald Trump. He has tried to destroy our institutions, one by one, undermining the judiciary, the press, the intelligence agencies, the universities. You look at every one of our major truth institutions, he’s trying to undermine them. Our system of checks and balances.”

The US Constitution seems on the verge of facing its most severe stress test since Watergate. But isn’t that antique document constraining the 45th president? Aren’t those checks and balances working? It is almost as if the Founding Fathers had powers of prophecy and anticipated a presidency like Trump’s. “The irony in all this is that the Founding Fathers were dealing with a mad king,” he laughs, recalling the lunacy of George III, the British monarch who lost America. “And we’re dealing with a mad president.”

Joseph Stiglitz in his office at New York’s Columbia University. The winner of this year’s Sydney Peace Prize, he says of Australia’s recent political stoushes: “Your car crashes are little nicks. America’s car crash is potentially fatal.”

Photo: Sasha Maslov/The New York Times

For much of his first year in office, Trump was stymied: unable to repeal and replace Obamacare, or enforce his travel ban targeting mainly Muslim nations. Late last year, however, he won passage of the country’s biggest tax cuts since the Reagan era. Stiglitz says it hurt the very people, the white working class, who put him in the White House. A majority of people outside the top 20 per cent and bottom 20 per cent of earners, he has calculated, will actually pay more tax.

“So much of my work has been about inequality, then they have a tax bill saying, ‘Let’s give more money to the people who are rich.’ So it’s a tax increase for people who have already been eviscerated to finance a tax cut for the billionaires. What sort of society does that when inequality is a major problem?”

Trump and top-flight CEOs such as Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs would argue the US economy is booming. That the tax cuts have boosted business and consumer confidence. That there’s been a Trump bump, even if the markets have hit a corrective speed bump in recent months. “Mostly this is the slow and eventual recovery from the Great Recession [the 2007- 09 Global Financial Crisis],” counters Stiglitz.

“Every recession eventually comes to an end, and restorative forces start to play. The engine is restarting. But just to put this in context, if you look at the other North American country, Canada, it’s done a lot better than America. Trudeau beats Trump. Our recovery is mediocre, just in the centre of the OECD average.

It was as a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1960s that Stiglitz started theorising about disparities in American wealth. “The subject of inequality was not talked about in any textbook at any level,” he remembers. “It still isn’t in most places!” His thesis, “The Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, became the basis for a body of work that in 2001 helped earn him the Nobel Prize.

Stiglitz’s Vanity Fair article “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%” cemented his status as a celebrity economist. “Wealth begets power,” he wrote, “which begets more wealth.”

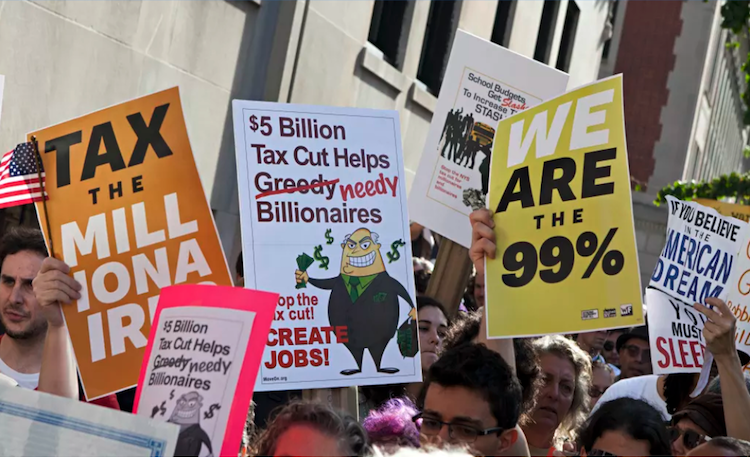

What cemented his status as a celebrity economist was a Vanity Fair article published in 2011 with the headline, “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%”. Stiglitz chronicled how this super-rich elite now controlled 40 per cent of American wealth, and how their incomes had soared 18 per cent in the previous decade while the middle class had seen their incomes fall. “Wealth begets power,” he wrote, “which begets more wealth.” He also reckoned that most Americans were living beyond their means.

The article’s catchy terminology came to enjoy an unexpected afterlife. Months later, when protesters formed the Occupy Wall Street movement, and erected a tent encampment amid the corporate skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan’s Financial District, their rally cry became, “We are the 99 per cent.”

Stiglitz’s chronicling of the wealth and power held by 1 per cent of the US population inspired the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement’s slogan, “We are the 99%.” Photo: AAP

It was the beginning of the social media era, Stiglitz says of the Vanity Fair essay, “so not many things had gone viral. It clearly showed the depth of concern about this issue. I hit a raw nerve in our society.”

Your intention wasn’t to launch a new class war, I say. “That article was trying to argue that there was a broad consensus about what should be done, rather than the traditional class warfare dynamic where it’s upper class versus the working class. Saying it was 99 per cent is a very different caricature.

“And then in the article I went on to say that it was in the enlightened self-interest of the 1 per cent to create a more equal society. Contrary to what Trump has been doing, I was trying not to divide our society but to try to say that there was a basis where we could all come together, and it was trying to persuade even the 1 per cent to join the rest. There was a very different tone. It was written to be non-divisive.”

Stiglitz had grasped the importance of bringing economic theory into the mainstream in the mid-1990s, when he worked in the Clinton Administration as the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. “Bill Clinton said, ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’ That aphorism caught reality. I realised you have to get popular understanding of these issues, you have to change mindsets.”

Perhaps this also explains Stiglitz’s manner. He wears his intellect lightly, and though he probably wouldn’t describe himself as a “popular economist”, that is essentially what he has become.

As US president from 1993 to 2001, Bill Clinton cast himself as a New Democrat, an attempt to find a “Third Way”, synthesising the government interventionism of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal with Ronald Reagan’s free-market conservatism. As a New Keynesian who believed government should correct the failings of the market, Stiglitz soon found himself locked in an ideological battle over the deregulation of Wall Street with figures such as Alan Greenspan, the then chairman of the US Federal Reserve, and Clinton’s treasury secretary, Robert Rubin, a former co-chairman of Goldman Sachs.

“I thought the evidence that financial market liberalisation led to instability was overwhelming and the evidence it led to more growth was underwhelming, and therefore argued that we ought to tread cautiously,” he says. “Globalisation was the same thing. I thought while there were strong arguments for the benefits when it’s well managed, there were strong arguments that a lot of people were being displaced, and could not on their own cope.”

After serving in the first term of the Clinton administration, Stiglitz turned down an invitation to continue in his post. It meant he was absent from the White House when in 1999 the Clinton Administration backed the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, “a decision which helped blow up the financial markets”. Enacted in the midst of the Great Depression, and intended to curb the kind of reckless speculation that had caused the 1929 Wall Street crash, this landmark legislation separated investment banks and commercial banks. Repealing it meant demolishing this firewall, which exposed commercial banks to the more risk-taking culture of investment banks. As a result, the appetite grew for the kind of derivatives that contaminated the whole banking sector and contributed to the 2008 crash and the Global Financial Crisis.

Perhaps if he had remained in the White House, I suggest, he could have helped avert this financial meltdown. “When I was there it didn’t happen,” he says, displaying that rabbinical smile again. “One could undermine it, one could explain why it was dangerous. It’s hard to enact when there’s strong opposition from the policy shop.”

But Stiglitz was no longer manning that shop. By now, he was serving as the chief economist of the World Bank. There his battles continued. With mounting horror, he observed how the West tried to foist “free-market fundamentalism” on developing countries, and how the World Bank did Wall Street’s bidding. However, when he raised these concerns, the US Treasury exerted enormous pressure on the World Bank to silence him. “It was a great disappointment,” he wrote at the time, “that my own government should have gone so much against the principles for which I believed it stood.” So in late 1999, he decided to return to academia.

For Stiglitz, the George W. Bush years started disastrously, with tax cuts that benefited corporations and the rich. “Seldom have so few gotten so much from so many,” he wrote despairingly at the time. Because the 2001 tax cuts did little to stimulate an economy reeling from the dotcom recession, the Federal Reserve adopted unprecedented low interest rates. This in turn led Americans to borrow more with laxer credit standards, which fuelled the growth in sub-prime mortgages.

Then came September 11 and the Iraq War, a “terrible mistake“, according to Stiglitz. The professor’s attempt to quantify the economic collateral damage led him and the Harvard academic Linda Bilmes to publish The Three Trillion Dollar War: The True Cost of the Iraq Conflict. It instantly became a bestseller, and was translated into 22 languages. When the Bush White House blasted Stiglitz for lacking the courage to consider the cost of doing nothing and the cost of failure, the economist hit back: “The White House lacks the courage to engage in a national debate about the cost of the Iraq War.”

The 2008 election of Barack Obama brought with it the hope of national renewal and economic revival, but the new president disappointed Stiglitz. The banks bailout rankled most, when Obama caved into pressure from Wall Street.

There was logic in the young president’s thinking. ” ‘The banking system is not working, the economy can’t work without banks. I can’t do banks, I have to rely on the bankers, so I better do what they say,’ ” explains the professor of Obama’s perspective. “I understand that mindset but I also understand it was holding us up for ransom. And I think it’s wrong, and other countries have done it better. And banking is not that complicated.”

Famously, Stiglitz wrote that an enterprising 12-year-old could have then made money running a bank following the implementation of the US government’s rescue plan. “You borrow money at 0 per cent and lend it back to the government at 3 per cent, and they got a bonus for doing that?” he says, with mock incredulity. “It was another example of trickle-down economics: ‘Give enough money to the banks and all of us will do well.’ And so I said he was continuing the Reagan tradition of trickle-down economics, which was a gross insult for a Democrat.” It was a case of privatising profits and nationalising losses, with bankers reaping the harvest and taxpayers footing the bill. The chasm between the rich and the rest grew even bigger.

Then US president Barack Obama in 2010: his bailout of Wall Street banks following the GFC was a disappointment, says Stiglitz: “He approached it from a very conservative viewpoint.”

Is Stiglitz suggesting Obama not only contributed to America’s economic segregation but accelerated it? “What I was really trying to say was that this was a moment where, with leadership, there was an understanding that our system wasn’t working and that if we’d had the right kind of leadership at that moment, we could have made dramatic changes in our economic system in the way that Franklin Roosevelt had done. You could have changed the tax law. There was momentum at that moment. Obama had both houses of Congress. He could have done a lot more. He approached it from a very conservative viewpoint.”

Other commentators argued that the response, however imperfect, was understandable: ahead of the bailout, there were fears customers would insert their bank cards into ATMs and be unable to withdraw any cash. For American capitalism, it truly was a Code Red moment.

Some of Stiglitz’s other theses have also drawn an acid shower of criticism, from his call for a flexible euro with a strong “northern euro” and softer “southern euro” (critics argued it would lead to even more economic chaos) to his assertion recently that Bitcoin should be outlawed because of the lack of adequate oversight (defenders of cryptocurrencies argue that all currencies are used for illegal activities).

Long-time admirers have taken issue with him, too. A fellow Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, who has described his friend Stiglitz as “an insanely good economist“, rejected his argument that inequality was an impediment to economic growth in the aftermath of the GFC because the rich have a lower propensity to spend than the rest. “I wish I could sign on to this thesis, and I’d be politically very comfortable if I could,” wrote Krugman in The New York Times in 2013. “But I can’t see how this works.”

Yet his progressive credentials rather than his stellar curriculum vitae explain his latest accolade, the 2018 Sydney Peace Prize, announced today.

The professor has been awarded 40 honorary degrees and various national honours, including being appointed to France’s Legion of Honour. Yet his progressive credentials rather than his stellar curriculum vitae explain his latest accolade, the 2018 Sydney Peace Prize, announced today. Previous recipients have included the Black Lives Matter campaigners, John Pilger, Noam Chomsky, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Arundhati Roy. The citation from Sydney University’s Sydney Peace Foundation commends him for “leading a global conversation about the crisis caused by economic inequality, for exposing the violence inflicted by market fundamentalism, and for championing just solutions to the defining challenge of our time“.

Stiglitz, who will deliver his prize lecture at Sydney Town Hall in November, has always enjoyed his travels to Australia, even if he was slightly perplexed while on a trip to Darwin that the local tabloid, the NT News, had such a fixation with crocs. He has also been intrigued, like so many economists globally, by Australia’s quarter-century run of recession-free growth. “You had two things going in your favour,” he says. “Resources and your location near China. Those weren’t guarantees for success, but they opened up opportunity.”

“Australia used to be one of the most equal countries in the world. It’s now below average for advanced nations. That was the result of a change in policies.”

What about Australia’s judicious regulation and careful oversight of the banks? His face remains impassive.

“Banking regulations, probably true. On the other side, Australia used to be one of the most equal countries in the world. It’s now below average for advanced nations. That was the result of a change in policies. It wasn’t inevitable, and I always say measuring GDP is not a good way to judge a country. It depends on what’s happening to the average citizen. And they haven’t fared as well because of the growth of inequality, and that was the result of government policy.”

Given his left-wing politics, I assume he will blame former Liberal PM John Howard’s WorkChoices reforms. But no. “It began before. It’s been long-standing. There was a little bit of the Third Way, New Democrat in Australian politics. They didn’t go as far in bank deregulation, but in labour market policy they actually went further than the US. The Australian system of arbitration was a system we would study, but you dismantled that, and you are now a model of what not to do.” Here he is referring to the Industrial Relations Reform Act of the mid-1990s, which led more disputes to be settled in the workplace and reduced the role of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission. “That was a big mistake.”

Only one Australian prime minster is singled out for praise. “Kevin Rudd’s management of the GFC was a textbook example of what to do. It was the best, most thought through response in the world.”

A criticism locally was that the 2009 stimulus package lavished a lot of money on giving schools a freshening up and handing out lump-sum cash payments that were spent quickly. “That was the intent,” he says, smiling. “It was thought through: ‘How do we get money going quickly? How do we deal with the problem in the medium and long term? A five-year road program is not going to solve today’s GFC.’ It was thought out in terms of the timing of the flows.”

What about Australia’s ongoing political recession, changing PMs with dizzying regularity, despite a prolonged period of economic success. Why so many political car crashes when the road conditions have been so good?

“Your car crashes are little nicks,” he shrugs. “America’s car crash is potentially fatal.”

Stiglitz (at right)at the UN in New York with former PM Kevin Rudd and Hungarian-American financier and philanthropist George Soros. Photo: AAP

The notion of American decline is almost as old as the republic itself. The Wall Street crash. The Great Depression. Vietnam. Watergate. The GFC. The US always seems to be going to hell but never quite gets there. This time, however, something does appear to have changed. A crisis of faith in the American dream: a loss of belief that middle-class children will enjoy more financially abundant lives than their parents.

This is old news to Stiglitz. What worries him now is that the political and economic dysfunction is diminishing America’s standing in the world. “China is the world’s largest trading economy, and the largest source of savings. The only thing we dominate is military.”

What about soft power? “American soft power was badly damaged by the Iraq War and Bush. The GFC damaged our soft power, too, because we were seen to have created an economic system that wasn’t working in a sustainable way. The growth of inequality in our economy has damaged our soft power. The persistence of discrimination. The pictures of police brutality which now go viral around the world. Mass shootings. All those harm our soft power. And let’s face it, Trump has done more to damage our soft power than anything else. There are only two countries around the world in which confidence in America is strong, Russia and Israel. And when those are your two cheerleaders, you ought to be worried.”

Could the US once more become the global exemplar? “I keep an open mind,” he says, smiling. “Obama’s election was testimony that the US was more racially open than people had thought, and that gave a big boost. The right president could retrieve America’s soft power.”

Just surviving Trump, he says, will be cause for celebration: “The fact that our institutions worked and protected us against an authoritarian, know-nothing president.”

Even in his mid-70s, Stiglitz shows little sign of slowing down. His suite of offices at Columbia University, manned by a squadron of keen young assistants, has a hive-like charge. He also remains politically engaged. Already he is eyeing up the 2020 presidential race, and the prospective candidates positioning themselves to take on Trump. Only that morning he had received an email from Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Democratic presidential hopeful, who has long shared his concerns about income inequality.

There’s a twinkle in the old man’s eyes as he prepares for the coming battle. It’s war, and Joseph Stiglitz will not rest until he has seen and served an American president who will champion the 99 per cent.